日本語版はこちら

Introduction: The Meaning of Historical Reconciliation in an Age of Division

The contemporary world is confronting deepening conflict and fragmentation. Hatred and cycles of retaliation arise between nations, among ethnic groups, and at times even within a single society, closing off the path to peace. How can we overcome these divisions and realize genuine reconciliation and coexistence? This essay seeks to offer a compelling answer to this fundamental question by examining the arduous yet hopeful journey of the Republic of Benin in West Africa.

Benin has carried the burden of being one of the central hubs of the transatlantic slave trade—one of the darkest chapters in human history. Yet the country has faced this past head-on and has become a leader in international reconciliation efforts. The lessons from Benin’s experience extend far beyond the historical relationship between Africa and the West. The nation’s process of acknowledging historical facts, admitting wrongdoing, and fostering mutual forgiveness offers invaluable insights for Japan and other Asian societies grappling with historical disputes and contemporary tensions.

1. Scars of History: The Structure of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Benin’s Place Within It

No discussion of reconciliation can begin without understanding the tragedy of the transatlantic slave trade—a system that, over centuries, robbed countless individuals of their lives and dignity and left deep wounds in intercontinental relations. Confronting this history was an indispensable starting point for Benin’s path toward reconciliation.

From the 16th to the 19th century, the kingdoms located in what is now the Republic of Benin—such as the Kingdom of Dahomey—formed the core of what Europeans called the “Slave Coast.” Alongside the violent abduction of people by European traders, a painful and complex reality existed: some African rulers delivered captives from interethnic conflicts to European buyers. From this region alone, an estimated 10 to 12 million people were forcibly transported to the Americas.

European “chattel slavery,” in which enslaved persons were treated as dehumanized property or livestock, differed fundamentally from systems of servitude found in parts of Africa, where enslaved individuals could sometimes marry or form families.

Ouidah, located in present-day southern Benin, functioned as the largest slave trading port in West Africa. Its unusually deep shoreline enabled heavily loaded ships to anchor for extended periods. Whereas ships could remain only briefly in other ports, Ouidah’s capacity made it a highly efficient trading hub.

It is crucial to note that the modern state of “Benin” did not exist during the period of the slave trade. Multiple kingdoms and empires—such as Dahomey and the Benin Empire—occupied this region, and their territories extended far beyond today’s national borders. Thus, attributing historical responsibility solely to the contemporary Republic of Benin would be inaccurate. This historical complexity made it necessary for later reconciliation efforts to involve not only Benin but the broader West African region.

2. Colonialism, Socialism, and Turmoil: How Political Transformations Prepared the Ground for Reconciliation

Following the abolition of the slave trade in the 19th century, European colonial expansion accelerated across Africa, and the Kingdom of Dahomey became a French colony. Although it achieved independence in 1960 as the Republic of Dahomey, a series of military coups over the next twelve years plunged the country into political instability.

In 1975, President Mathieu Kérékou renamed the nation the “People’s Republic of Benin.” The name “Dahomey” derived from a kingdom associated with active participation in the slave trade; replacing it signaled an intention to sever ties with that negative legacy and to reflect a broader regional cultural identity.

The socialist, Marxist–Leninist system adopted by the new republic ultimately resulted in economic collapse. Over fifteen years, the country fell into severe poverty—a period later remembered as the “nightmare years.” Yet this prolonged internal suffering created the social and psychological conditions necessary for transformation. The crisis awakened a collective desire for renewal, laying the foundation for a national commitment to reconciliation.

3. Step-by-Step Construction of the Reconciliation Process: From Political Healing to Historical Healing

Benin’s reconciliation strategy was a long-term, deliberate, multi-stage effort: first resolving domestic political divisions, then confronting the historical trauma of the slave trade. This staged approach—establishing national unity before addressing painful historical issues—proved essential to the success of the entire process.

(1) The 1990 National Conference: Healing Internal Political Divisions

In the late 1980s, faced with national bankruptcy and mounting public pressure, the government renounced Marxism–Leninism in December 1989. In 1990, representatives from all sectors of society gathered for a National Conference that became a turning point for both political reform and later historical reconciliation.

A ten-day dialogue between President Kérékou and Archbishop Isidore de Souza, the representative of religious leaders, marked a historic breakthrough. Kérékou publicly acknowledged the failures of his socialist policies and asked the nation for forgiveness. Archbishop de Souza urged the people to accept this apology. Their exchange of confession and forgiveness brought about political reconciliation and signaled “the beginning of reconciliation and development” in Benin.

(2) UNESCO’s “Slave Route Project”: Establishing Historical Truth

Building on political reconciliation, Benin turned to addressing historical wounds. Under President Nicéphore Soglo, who took office in 1991 after democratization, UNESCO launched the international project “The Slave Route” in 1994. Its aim was to objectively uncover the historical truth of the slave trade through academic and expert collaboration.

As part of the initiative, Ouidah—once a hub of the slave trade—became the site of the “Gate of No Return,” a memorial honoring those who never returned to their homeland.

(3) Kérékou’s National Apology: A Spiritual Framework for Reconciliation

Re-elected in 1996, President Kérékou advanced reconciliation further. He believed that the root cause of national stagnation was not simply economic but spiritual—what he called “spiritual underdevelopment,” meaning an inability to acknowledge one’s wrongdoing. This, he argued, hindered national development more seriously than material shortages.

For Kérékou, true national progress required both internal peace and moral accountability for historical responsibility. Thus, reconciliation became not merely a political program but a spiritual undertaking.

In 1998, he established a “National Day of Forgiveness” and symbolically renamed the “Gate of No Return” as the “Gate of Return,” signaling a welcome to the descendants of those who had been taken away.

In 1999, with the backing of West African leaders and traditional chiefs, Kérékou traveled to the United States and formally apologized on behalf of West African peoples for their ancestors’ participation in the slave trade.

This unprecedented act—an African leader acknowledging his own side’s role—stunned the international community. U.S. President Bill Clinton praised the apology, and the White House established the “One America” office for racial reconciliation. Bipartisan members of Congress later attended the 1999 International Conference in Cotonou, demonstrating the far-reaching impact of Benin’s efforts.

These actions were far more than political gestures. They were painful yet sincere attempts to rebuild the nation’s identity through the honest acceptance of historical responsibility.

4. The “Benin Model”: Three Principles of Reconciliation and Their Global Development

President Kérékou’s motivation for reconciliation was rooted in his Christian convictions: a failure to acknowledge wrongdoing becomes a spiritual barrier to national development. He believed that sincere apology for the “collective sin” of the slave trade was the only way to release the nation from this moral bondage.

This philosophy culminated in the 1999 International Conference of Leaders for Reconciliation and Development held in Cotonou, where what later became known as the “Benin Model” was established.

Leaders from across West Africa—including President Jerry Rawlings of Ghana—and traditional kings attended. Remarkably, around 100 bipartisan U.S. members of Congress also traveled at their own expense, stating, “Benin is doing what we have long asked our own government to do. We must join them.”

Their presence testified to Benin’s moral credibility.

Three Principles of the Benin Model

Through five days of discussions, three core principles were articulated—not slogans, but actionable guidelines for reconciliation:

1. Recognition of historical facts

Concealing or distorting history fuels future conflict. Reconciliation begins with an objective, shared understanding of the truth.

2. Acknowledgment of wrongdoing

Avoiding responsibility is a sign of “spiritual underdevelopment,” as Kérékou argued. Courageous admission of one’s collective wrongdoing is the first step toward reclaiming dignity.

3. Mutual forgiveness and breaking the cycle of hatred

Only through reciprocal forgiveness—victims forgiving perpetrators, and perpetrators forgiving themselves—can generations of accumulated anger and resentment be reversed.

Based on these principles, a groundbreaking resolution of mutual acknowledgment was adopted:

・Africans on the continent: Acknowledge that our ancestors took part in the slave trade.

・Europeans: Accept full responsibility for the trade.

・Euro-Americans: Admit culpability for expanding and perpetuating the system.

・African descendants of the diaspora: Accept these apologies and forgive both European traders and the African collaborators involved.

Following the conference, museums in Benin removed displays claiming that African kings bore no responsibility and that all blame lay with Europeans. The national narrative shifted “from excuses to truth.”

5. The Global Impact of the Benin Model: Universal Lessons for Overcoming Division

The reconciliation framework established by Benin did not end as a single event. It continued through sustained initiatives that earned broad international recognition.

Benin’s ambassador to the United States, Cyrille Oguin, visited all 50 U.S. states to share the significance of the Cotonou resolution. In 2002, the “Benin International Gospel & Roots Festival” brought together members of the African diaspora, reconnecting them with their heritage through culture and art.

The sincerity of Benin’s reconciliation efforts resonated far beyond Africa—particularly in the United States, where racial divisions have deep historical roots. The notion of an African leader acknowledging his ancestors’ role offered a new model of courage, hope, and moral leadership.

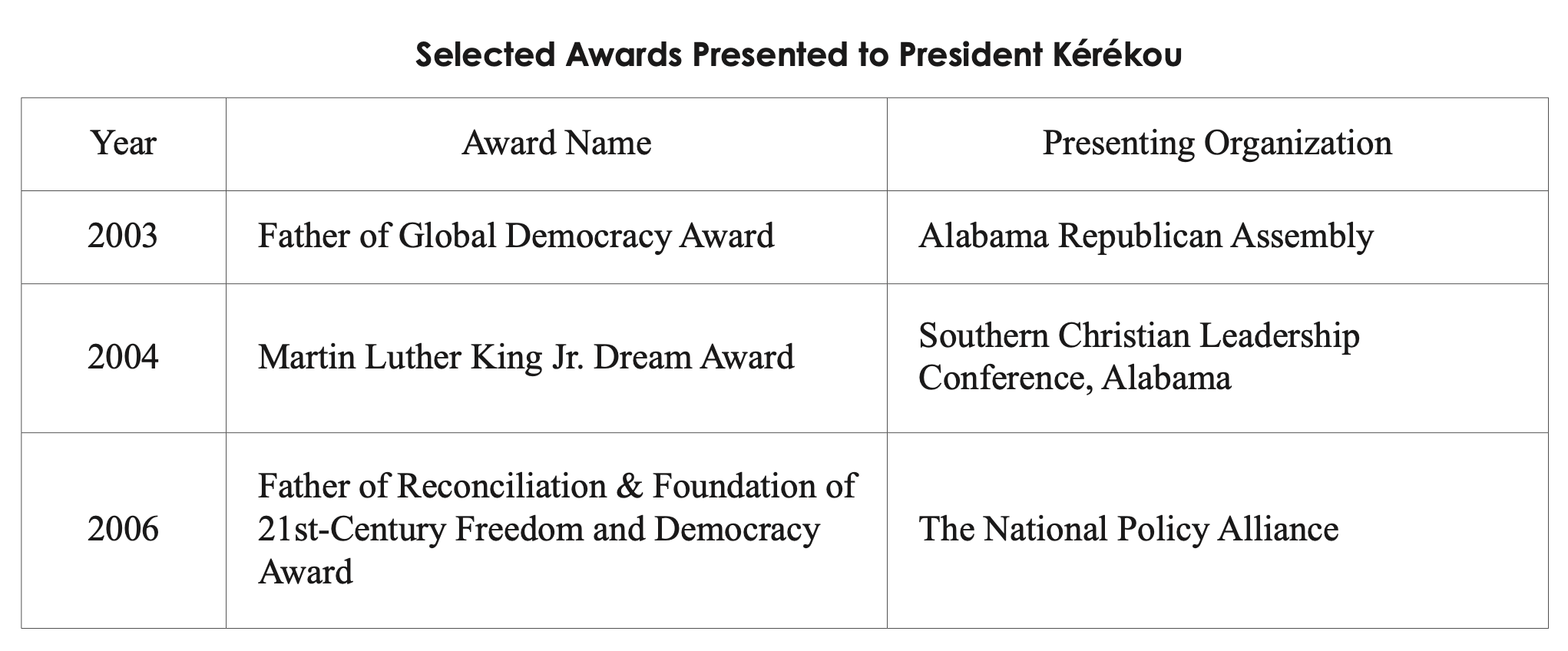

These honors testify that the Benin Model is not merely an African achievement but a contribution of universal value.

Universal Lessons

・The power of leadership: Transformative national change requires leaders willing to take moral risks.

・The link between moral repair and development: Unaddressed historical injustices can impede national progress.

・The value of clear principles: The three-step framework—truth, acknowledgment, forgiveness—provides a structured, replicable method for healing deep-seated conflicts.

Conclusion: From Overcoming the Past to Creating the Future

The Republic of Benin transformed a heavy historical burden—its central role in the transatlantic slave trade—into a model for global peacebuilding through sincere national apology and reconciliation. Its journey demonstrates that even from the darkest chapters of history, stories of hope and renewal can emerge.

The extraordinary leadership of President Kérékou and the three principles articulated at the Cotonou Conference showed the world the universal value of confronting historical truth, accepting responsibility, and breaking cycles of hatred through mutual forgiveness.

The renaming of the “Gate of No Return” to the “Gate of Return,” at the very place where enslaved Africans once departed forever, stands as a powerful symbol: humanity can transform despair into hope. Benin’s experience offers a universal message—that even the deepest divisions and most painful historical antagonisms can be overcome through truth, sincere apology, and the courage to forgive.

May the legacy of Benin inspire each of us to become agents of reconciliation—in our own societies and in the world at large.

This article is based on an interview conducted by the Institute for Peace Policies with the author of Beginning with Benin: From Reconciliation to Peace, which was officially added to the collection of the National Diet Library of Japan in January 2023 and is also registered in CiNii. For details, see: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BD04750234

References

Gbevegnon, E. (2022) Beginning with Benin from Reconciliation to Peace: An Account of The Goodwill Ambassador’s Efforts and Development for the Reconciliation Movement. Bandai Hō Shobō.