EN-ICHI Opens Up the Future of Family and Community

The Evolution of Japan’s Foreign National Acceptance Policy

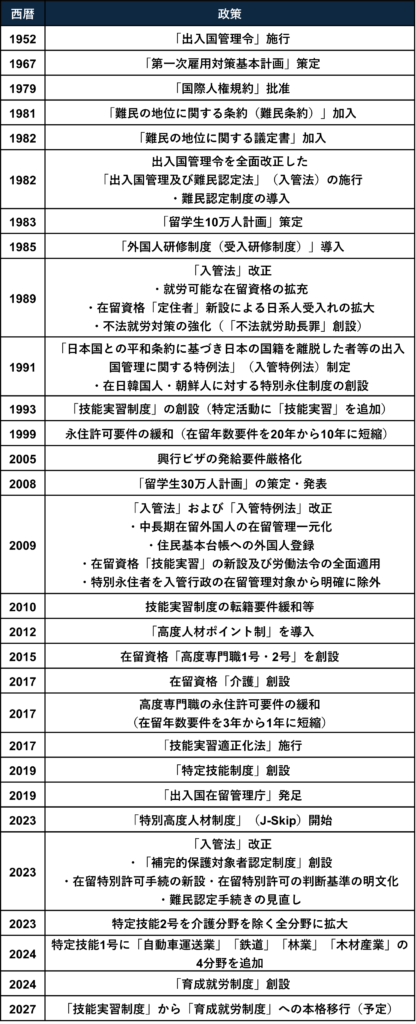

In the postwar period, Japan has long upheld the principles of “not adopting immigration policy” and “taking a cautious approach toward the acceptance of so-called unskilled workers.” Since the 1990s, however, as population aging and labor shortages have become structural challenges, Japan’s institutional framework has been gradually expanded. Today, foreign human resources policy is increasingly oriented toward employment, settlement, and social coexistence. This paper traces the evolution of Japan’s foreign human resources acceptance policy in chronological order, focusing on major legal reforms and the creation of new systems, while examining their background, social impact, and current status.

- The 1950s–1960s: Establishment of the “Not Adopting Immigration Policy” Principle

- The 1970s–1980s: Institutionalization of Refugee Acceptance and the Start of “De Facto” Foreign Labor Acceptance

- The 1990s: Comprehensive Immigration Law Reform and Transition to “Full-Scale Acceptance”

- The 2000s: Expansion of Settled Foreign Communities and Institutional Development of Management and Coexistence

- The 2010s: High-Skilled Talent, New Sectors, and a Turning Point Toward “Immigration Policy”

- The 2020s: Expansion and Reorganization—SSW Expansion, Abolition of TITP, Refugee Reform

- From 2025 Onward: Toward “Orderly Coexistence”

- Conclusion: How Will Japan Engage with an “Immigration Society”?

The 1950s–1960s: Establishment of the “Not Adopting Immigration Policy” Principle

The basic framework for accepting foreign nationals in postwar Japan was formed by the "Immigration Control Order", enacted in 1951 and enforced in 1952, later revised into the "Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act" (hereinafter, the Immigration Control Act). At the time, the majority of foreign residents in Japan were individuals from former Japanese colonies—primarily Korea and Taiwan—who had resided in Japan since before the war. Both institutionally and politically, the idea of actively accepting foreign labor to support domestic industries was highly limited.

As Japan’s high-growth economy progressed, industry began to voice the need to secure additional labor, and by the mid-1960s requests emerged to accept foreign unskilled workers. Nevertheless, the government reaffirmed in the "First Employment Measures Basic Plan" (1967) that “unskilled workers will not be accepted.” This policy stance has been consistently maintained to the present day. At that time, large-scale internal migration from rural to urban areas allowed labor supply and demand to be adjusted domestically, enabling Japan to avoid reliance on foreign labor.

The 1970s–1980s: Institutionalization of Refugee Acceptance and the Start of “De Facto” Foreign Labor Acceptance

In the late 1970s, Japan confronted the arrival of Indochinese refugees. Following the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, refugees known as “boat people” began arriving on Japan’s shores. Initially reluctant to accept refugees, Japan faced growing humanitarian pressure and reputational concerns from the international community. After the establishment of the "Coordination Council for Vietnamese Refugee Measures" in September 1977, Japan gradually developed an acceptance framework, including a commitment to accept a certain number of refugees for permanent settlement.

Japan further ratified the "International Covenants on Human Rights" in 1979 and acceded to the "Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees" in October 1981 and its Protocol in January 1982. Consequently, the "Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act" came into force on January 1, 1982, introducing a formal refugee recognition system that enabled asylum applications and legal residence (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Beginning of Japan’s Refugee Policy

Source: Compiled by the author

At the same time, domestic labor demand began to change. While maintaining the official position of not accepting unskilled workers, Japan saw an increase in foreign workers through entertainment visas, the return of descendants of Japanese nationals left behind in China, and the expansion of international students under the “100,000 International Students Plan” (1983).

Following the Plaza Accord in 1985, rapid yen appreciation caused acute labor shortages in small and medium-sized enterprises and construction, particularly in so-called “3K” jobs (dirty, dangerous, and demanding in Japanese words). As a result, during the late 1980s, cases of overstaying and unauthorized employment increased, bringing foreign labor acceptance to the forefront as a policy issue.

The "Sixth Employment Measures Basic Plan" (1988) formally distinguished between “professional and technical workers,” whose acceptance should be appropriately addressed, and “unskilled labor,” whose acceptance should be approached with extreme caution (Figure 2). This framework became the standard government position. In practice, however, labor demand drove continued inflows, entrenching a policy of “not accepting immigrants in principle, but accepting them in reality.”

Figure 2: Direction of Foreign Worker Acceptance in the "Sixth Employment Measures Basic Plan"

-1.png)

Source: Compiled by the author

The 1990s: Comprehensive Immigration Law Reform and Transition to “Full-Scale Acceptance”

Amid severe labor shortages during the bubble economy and accelerating globalization, Japan undertook its first comprehensive reform of immigration law in the postwar era in 1989. While maintaining the principle of “actively accepting highly skilled workers while not permitting unskilled labor,” the reform substantially expanded acceptance frameworks to supplement labor shortages (Figure 3).

First, residence statuses allowing employment were significantly expanded in professional and technical fields. Second, the “Long-Term Resident” status was newly established, primarily targeting up to third-generation descendants of Japanese nationals, with virtually no employment restrictions. This enabled large numbers of Nikkei workers from Brazil and Peru to engage in manufacturing and construction, marking a turning point in which foreign workers became embedded in regional labor markets. In addition, the offense of “Promoting Illegal Employment” was introduced, clearly establishing employer liability for illegal employment.

Figure 3: Key Points of the 1989 Immigration Law Reform

Source: Compiled by the author

Although the reform did not open the door to unskilled labor, strong demand persisted. In 1990, the Ministry of Justice authorized the acceptance of trainees by small and medium-sized enterprises through ministerial notifications. This led to the creation of the "Technical Intern Training Program" (TITP) in 1993, jointly administered by the former Ministry of Labour and the Ministry of Justice. The program enabled trainees to work as interns after training, institutionalizing the dispatch of foreign workers to production sites.

In 1991, the "Special Act on the Immigration Control of Those Who Have Lost Japanese Nationality pursuant to the Treaty of Peace with Japan" (hereinafter, the Special Act) was enacted, granting Special Permanent Resident status to long-term Korean and other residents. This law legally secured their permanent residence and clarified the postwar status of long-term foreign residents.

In the late 1990s, labor demand temporarily declined due to the Asian Financial Crisis and domestic financial instability. Nevertheless, policies encouraging settlement emerged, including relaxed permanent residence requirements in 1999.

Overall, the 1990s marked the period when Japan began accepting foreign nationals as part of society, while challenges such as language barriers, education for foreign children, and cultural friction became increasingly visible. The term “multicultural coexistence” gained nationwide usage during this time. Criticism of the Technical Intern Training Program also intensified due to the gap between its stated purpose of human resource development and its reality as a source of low-wage labor.

The 2000s: Expansion of Settled Foreign Communities and Institutional Development of Management and Coexistence

In the 2000s, population decline and aging became tangible realities, making long-term labor force strategies imperative. Settled foreign residents began to take root in local communities, prompting municipalities to explore multicultural coexistence policies, including language support and multilingual services.

Institutionally, scrutiny and operation of the Entertainer Visa were tightened from 2005 to curb trafficking-like employment and illegal overstays. Student policy was strengthened, culminating in the “300,000 International Students Plan” in 2008, aimed at linking education to high-skilled employment.

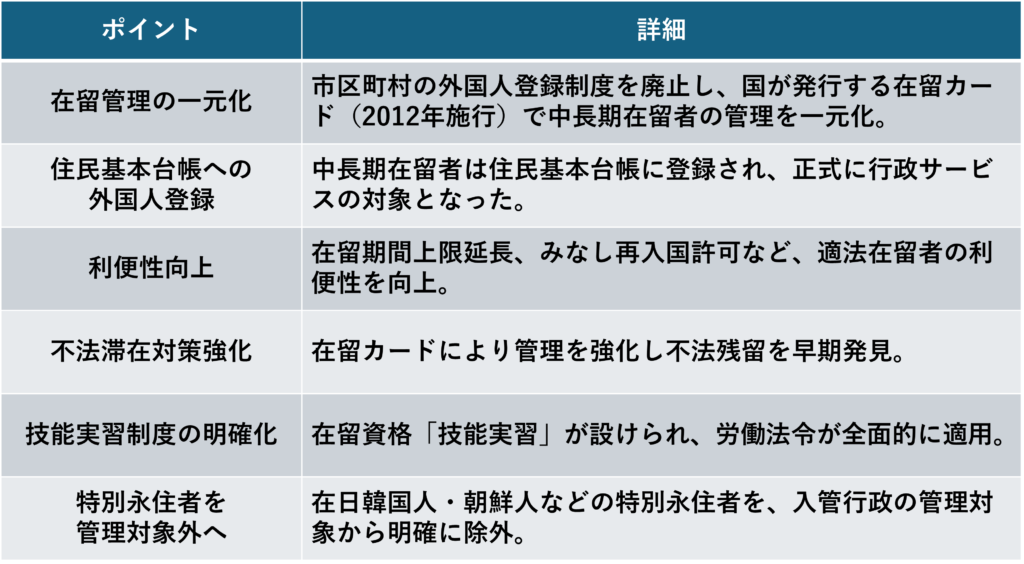

The 2009 amendments to the Immigration Control Act and the Special Act represented a major modernization of immigration administration (Table 1). The municipal foreign resident registration system was abolished and replaced by a centralized Residence Card system issued by national authorities. Convenience for lawful residents was improved, while enforcement against illegal stay was strengthened. Mid- to long-term residents were added to the Basic Resident Register, formally integrating foreign residents into administrative services. The amendments also clarified the legal framework for technical interns by creating the residence status “Technical Intern Training,” applying full labor laws from the first year. Special Permanent Residents were removed from immigration control administration, clearly separating them from the Immigration Control Act.

Table 1: Key Points of the 2009 Immigration Law Reform

Source: Compiled by the author

The 2009 global financial crisis revealed vulnerabilities in foreign employment policy, as repatriation assistance was provided to unemployed Nikkei workers, drawing criticism as short-term, cyclical policy. Persistent issues within the Technical Intern Training Program, including disappearances and human rights violations, drew international scrutiny, prompting partial reforms but leaving structural problems unresolved.

The 2010s: High-Skilled Talent, New Sectors, and a Turning Point Toward “Immigration Policy”

As Japan entered the 2010s, labor shortages became increasingly severe, and momentum grew to position foreign human resources as a central pillar of the country’s growth strategy. In 2012, the Points-Based Preferential Immigration Treatment System for Highly Skilled Foreign Professionals was introduced. Under this system, points were awarded based on criteria such as educational background, professional experience, income level, and age, and preferential measures were granted, including relaxed requirements for permanent residence and family accompaniment. In 2015, the residence status “Highly Skilled Professional” was established, further easing requirements and advancing Japan’s response to intensifying international competition for highly skilled talent.

A symbolic policy shift occurred in 2017, when a residence status for the nursing care sector was created and nursing care occupations were added to the Technical Intern Training Program, thereby institutionally opening a field that had long been closed to foreign workers. In the same year, the Technical Intern Training Act came into force, transforming the Technical Intern Training Program from a scheme based on ministerial notifications into one with a clear statutory foundation. This reform introduced a licensing system for supervising organizations that arrange the acceptance of technical interns, implemented external auditing mechanisms, and established Technical Intern Training (iii) in addition to the existing (i) and (ii) categories. For certified “excellent” training organizations, these changes expanded acceptance quotas and extended the maximum training period.

The most significant institutional transformation, however, was the creation of the Specified Skilled Worker (SSW) Program in 2019. In labor-shortage sectors such as food service, nursing care, construction, and agriculture, the program allows foreign nationals who pass designated skills tests and demonstrate a certain level of Japanese language proficiency to work for up to five years under SSW (i) status. Furthermore, SSW (ii), intended for more experienced workers, permits indefinite renewal of residence and family accompaniment. Although initially limited to two sectors, its scope was later expanded. Whereas the Technical Intern Training Program had been framed under the nominal purpose of “human resource development and international contribution,” the Specified Skilled Worker program explicitly accepts foreign nationals as labor, marking Japan’s official step toward accepting unskilled workers. During the same period, immigration administration was reorganized into the Immigration Services Agency, strengthening an integrated framework for acceptance, management, and coexistence.

The 2020s: Expansion and Reorganization—SSW Expansion, Abolition of TITP, Refugee Reform

Although the acceptance of foreign nationals stagnated in 2020–2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the relaxation of border control measures from 2022 onward led to the resumption of entry by international students and technical intern trainees, and the number of foreign workers began to increase again. Against the backdrop of chronic labor shortages, the Specified Skilled Worker (SSW) Program has been steadily expanded. In 2023, the scope of industries eligible for SSW (ii) was significantly broadened, making pathways toward long-term settlement—such as family accompaniment, unlimited renewal of residence status, and the possibility of permanent residence—much clearer. Furthermore, in 2024 additional sectors were added to SSW (i), enabling the system to expand flexibly in response to labor market needs (Figure 4). The government has also begun to set projected acceptance targets, reinforcing the direction of institutionalizing the SSW program as a core labor market mechanism.

Figure 4 : Sectors Covered by the Specified Skilled Worker Program (as of December 2025)

-scaled.png)

Source: Created by the author based on Immigration Services Agency (2025b, p. 6)

With regard to highly skilled professionals, the "Special Highly Skilled Professional System" (J-SKIP) was launched in 2023. Under this scheme, individuals who meet certain criteria can be granted Highly Skilled Professional (i) status without being subject to the points-based evaluation system. However, these measures have not necessarily led to a substantial increase in the intake of new highly skilled professionals, and international competition for global talent continues to intensify.

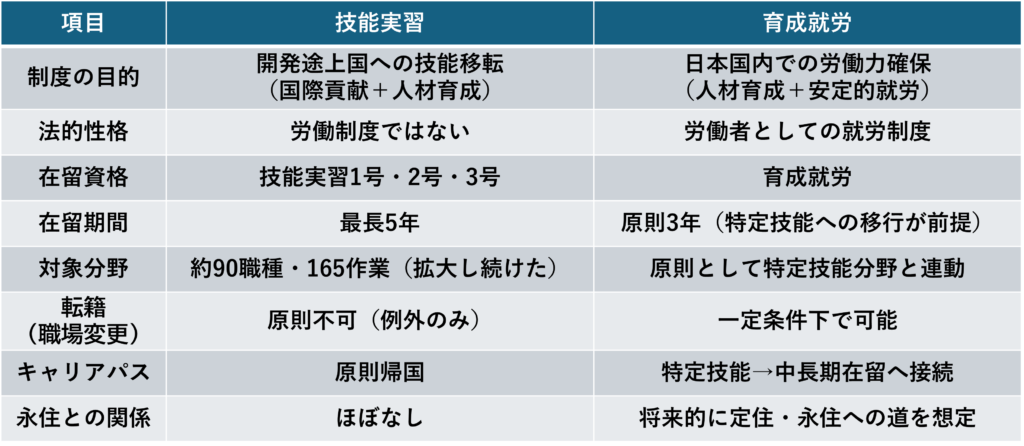

Meanwhile, the "Technical Intern Training Program" (TITP) has moved toward a fundamental overhaul in response to repeated cases of misconduct, human rights violations, and trainee disappearances. From the end of 2022, deliberations on reform were conducted by an expert panel, and the final report released in 2023 clearly called for the abolition of the existing program and the creation of a new system more aligned with on-the-ground realities. In 2024, related legislative amendments were enacted, officially deciding to abolish the Technical Intern Training Program, which had continued for nearly 30 years. In its place, a new residence status, “Developmental Employment,” was established, with the "Developmental Employment System" scheduled to begin in 2027.

The new system aims both to develop human resources with skills equivalent to the Specified Skilled Worker (i) level and to secure workers for sectors facing labor shortages. Crucially, it represents a decisive shift in purpose—from the previous nominal emphasis on “international contribution” to a clear focus on domestic labor supply in Japan. In terms of system design, a “two wheels of a cart” structure is envisioned, whereby individuals complete up to three years of developmental employment in principle and then transition smoothly to Specified Skilled Worker (i) status. Through this arrangement, the policy framework is being reorganized to facilitate long-term employment and settlement (Table 2).

Table 2: Comparison of the "Technical Intern Training Program" and the "Developmental Employment System"

Source: Compiled by the author

Developments were also observed in the area of refugee and detention policy. Against the backdrop of international and domestic criticism over Japan’s low refugee recognition rates and the prolonged detention of asylum seekers, the 2023 amendment to the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act introduced several major changes. These included the establishment of the Complementary Protection Status Recognition System, the systematization of application procedures for Special Permission to Stay, and the introduction of the Supervision Measures System as an alternative to detention. At the same time, changes to the treatment of the suspensive effect of deportation during refugee recognition procedures have raised human rights concerns. Nevertheless, the amendment is positioned as a reform aimed at preventing abuse of the asylum system and ensuring the sustainability of refugee procedures.

From 2025 Onward: Toward “Orderly Coexistence”

The Takachi administration, which took office in 2025, has advocated the vision of an “orderly coexistence society.” While acknowledging the necessity of accepting foreign human resources, it has emphasized strict responses to illegal activities and violations of rules. As foreign workers are becoming increasingly indispensable to Japan’s economy and local communities, the administration’s distinctive stance lies in placing strong emphasis on stricter policy implementation and the maintenance of public order, with the aim of curbing the growing sense of public anxiety and perceived unfairness among citizens. At the same time, the government has remained cautious about explicitly referring to its approach as an “immigration policy.” While suggesting the possibility of setting certain upper limits on the number of foreign nationals to be accepted, it continues to uphold a pragmatic position of accepting foreign workers “to the extent necessary within a lawful framework.”

Meanwhile, as a growing number of foreign residents establish their livelihoods and assume roles as members of local communities, policy considerations can no longer be confined to labor market measures alone. Comprehensive coexistence policies encompassing education, healthcare, housing, social security, local communities, public safety, and social integration have become indispensable. The "Comprehensive Measures for Acceptance and Coexistence of Foreign Human Resources", which have been formulated and revised since 2018, will continue to be a focal point in future revisions—particularly in terms of how to balance expanded acceptance with the maintenance of order, and how far to advance institutional design premised on long-term settlement.

Conclusion: How Will Japan Engage with an “Immigration Society”?

In the postwar period, Japan has long maintained the official stance that it is “not an immigration country.” However, as successive systems—such as trainee and technical intern programs, the Long-Term Resident status, international student programs, and the Specified Skilled Worker scheme—have accumulated over time, the social reality has increasingly come to resemble that of an immigration society. The 2020s represent a period of major transition, marked by the expansion of the Specified Skilled Worker program and the abolition of the Technical Intern Training Program alongside the creation of the Developmental Employment system. During this period, Japan’s foreign national acceptance policy is gradually shifting its focus from “temporary labor” toward “human resource development, long-term settlement, and coexistence.” Looking ahead, the success or failure of policy will depend on how far Japan can move beyond acceptance as a mere tool for labor market adjustment and instead design integration policies that maintain social order while enabling diverse residents to live securely and with confidence.

Table 3 :Major Policies on the Acceptance of Foreign Nationals

Source: Compiled by the author

References

- Eba, H. (2024). Kokusai rodo ido ni okeru ginō to kokusai kyōryoku no kanōsei: Ijū rōdōsha no ginō keisei to ijū kanren katsudō no ODA tekikakusei ni tsuite [Skills in international labor migration and the potential for international cooperation: Skill formation of migrant workers and the ODA eligibility of migration-related activities]. IPSS Working Paper Series (No. 73). National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

- Eba, H. (2025). OECD rebyū kara kōsatsu suru Nihon no gaikokujin rōdōsha ukeire no genjō [The current state of Japan’s acceptance of foreign workers as examined through OECD reviews]. Nenkin to Keizai (Pensions and the Economy), 44(1), 31–41.

- Kashiwazaki, M. (2023). Nihon no “nyūkoku kanri” taisei: Jisshitsuteki imin seisaku to seido-ka sareta jinken shingai o tou [Japan’s “immigration control” regime: Questioning de facto immigration policy and institutionalized human rights violations]. Kikan Keizai Riron (Quarterly Journal of Economic Theory), 60(2), 6–20.

- Kato, J. (2024). Ginō jisshūsei ga hi-seiki imin ni naru yōin: Seido no mokuteki kara kairi suru jittai [Why technical intern trainees become irregular migrants: The gap between institutional objectives and actual practice]. Mukogawa Literary Review, 61, 31–45.

- Kamibayashi, C. (2024). Imin ukeire to sengo Nihon no seisaku tenkan: Nyūkoku kanri seisaku to rōdōryoku kakuho seisaku o chūshin ni shite [Immigrant acceptance and postwar policy transformation in Japan: Focusing on immigration control policy and labor force policy]. DIO, 393, 8–12.

- Korekawa, Y. (2025). Nippon no imin: Fue tsuzukeru gaikokujin to dō mukiau ka [Immigrants in Japan: How should Japan respond to the growing foreign population?]. Chikuma Shobo.

- Kondo, A. (2022). Imin tōgō seisaku shisū (MIPEX 2020) nado ni miru Nihon no kadai to tenbō [Challenges and prospects for Japan as seen through the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX 2020)]. Imin Seisaku Kenkyū / Migration Policy Review, 14, 9–22.

- Immigration Services Agency of Japan. (2025a). Ikusei shūrō seido no gaiyō [Overview of the developmental employment system]. Retrieved January 7, 2026, from https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001452485.pdf.

- Immigration Services Agency of Japan. (2025b). Gaikokujin jinzai no ukeire oyobi kyōsei shakai jitsugen ni muketa torikumi [Initiatives for the acceptance of foreign human resources and the realization of a coexistence society]. Retrieved January 7, 2026, from https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001335263.pdf

- Takahata, S. (2015). Jinkō genshō jidai no Nihon ni okeru “imin ukeire” to wa nani ka: Seisaku no hensen to teijū gaikokujin no kyojū bunpu [What does “immigrant acceptance” mean in Japan in an era of population decline? Policy transitions and the residential distribution of settled foreign residents]. Kokusai Kankei / Hikaku Bunka Kenkyū (Journal of International Relations and Comparative Cultural Studies), 14(1), 141–157.

- Nagayoshi, K. (2020). Imin to Nihon shakai: Dēta de yomitoku jittai to shōraizō [Immigration and Japanese society: Understanding realities and future prospects through data]. Chuo Koron Shinsha.

- Higuchi, N. (2023). Imin seisaku o meguru renritsu hōteishiki: Tokutei ginō ni itaru keiro kara kangaeru [The system of equations surrounding immigration policy: Examining the pathway toward the Specified Skilled Worker program]. Global Concern, 5, 22–32.

- Miyoshi, N. (2025). Imin risuku [Immigration risk]. Shinchosha.

- Menju, T. (2024). Jichitai ga hiraku Nihon no imin seisaku (2nd ed.) [Local governments opening the path for Japan’s immigration policy]. Akashi Shoten.

- Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. (2009). Gaikokujin rōdōsha no koyō jittai to shūgyō, seikatsu shien ni kansuru chōsa [Survey on the employment situation of foreign workers and support for work and daily life] (JILPT Research Series No. 61). Retrieved January 7, 2026, from https://www.jil.go.jp/institute/research/2009/documents/061.pdf