EN-ICHI Opens Up the Future of Family and Community

Series: The Human Life Cycle and the Family (2) Human Birth and Characteristics of Brain Maturation

In the previous article, I introduced the first half of Chapter 5 from the classic work “Evolution of the Brain” by the renowned neurophysiologist Sir John Eccles. There, Eccles described the evolution of the limbic system and pointed out that, in humans, regions of the amygdala—particularly those sensitive to positive emotions—had expanded. At the end of the previous article, I also mentioned that during the era of Homo habilis, the brain volume of early humans exceeded that of the great apes.

- Temporal Gap Between Brain Evolution and the Emergence of Language Use

- The Human Infant as a “Fetus”

- Why Human Babies Are “Like Fetuses”

- The Human Brain Grows Fourfold

Temporal Gap Between Brain Evolution and the Emergence of Language Use

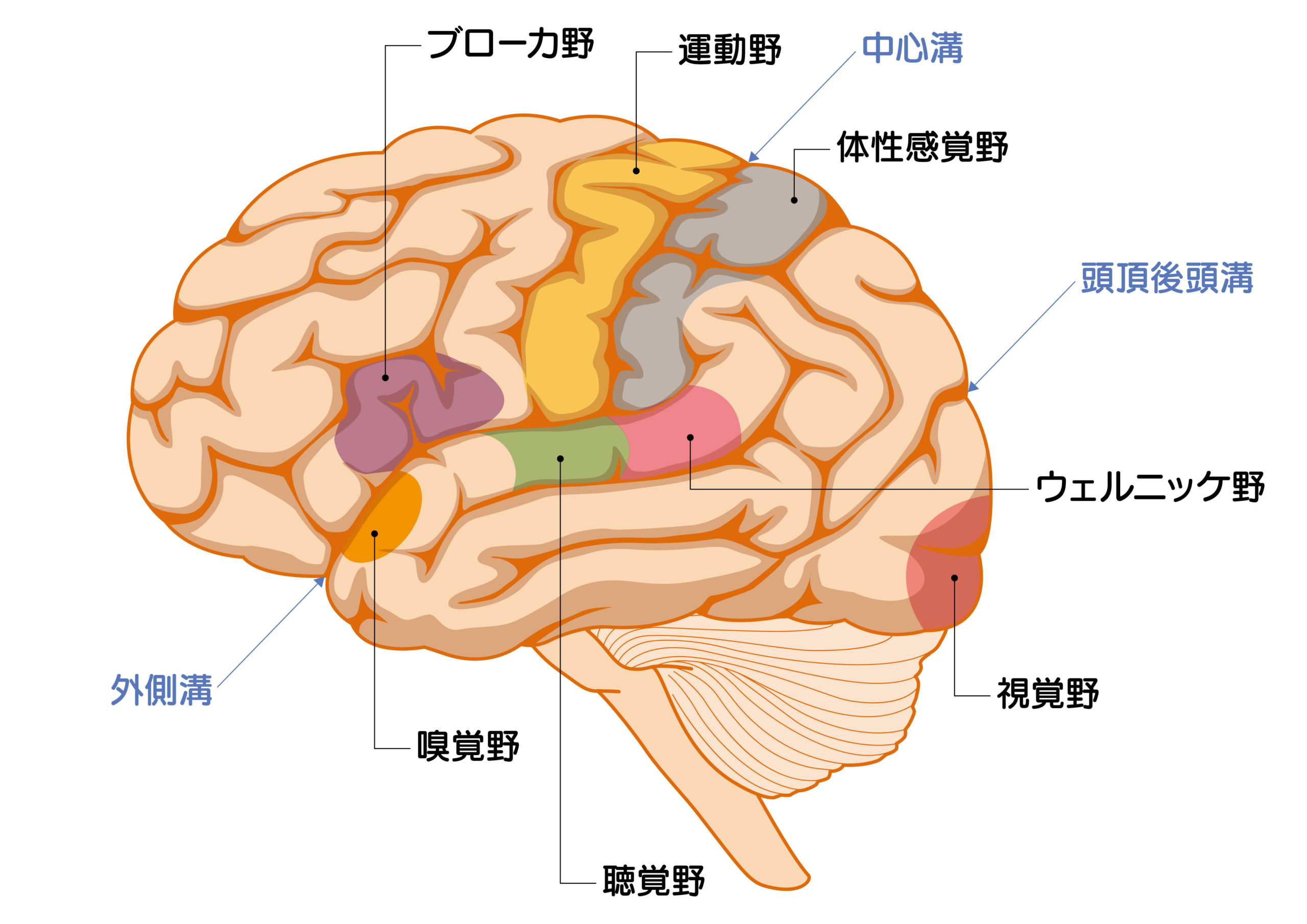

Eccles discusses Homo habilis in Chapter 2 of “Evolution of the Brain,” which gives an overview of human evolution. He states that the increase in brain size represented a major evolutionary advance, accompanied by the development of stone tool culture. As a result, they were granted the status of belonging to the genus Homo. The species name habilis (meaning “handy”) reflects their dexterity in creating tools. According to the fossil record presented by Eccles, from Australopithecus to Homo habilis, brain volume increased by about 30–40%. More importantly, there were also morphological changes: the lower parts of the frontal and parietal lobes expanded, corresponding to what are now recognized as the language areas—the anterior Broca’s area and the posterior Wernicke’s area. Eccles speculates that Homo habilis likely possessed both the neural foundations and the peripheral anatomical capacity necessary for speech.

Figure 1: Language Areas of the Modern Human Brain

Image: illustAC

However, because language use leaves no direct fossil traces, the evolutionary process of linguistic ability remains uncertain. It is generally believed that humans began to use language freely only around 50,000 years ago—a period often referred to as the “Cultural Big Bang,” when a sudden explosion of cultural innovation occurred. Therefore, there appears to be a temporal gap, on the order of millions of years, between the structural evolution of the brain’s language areas as seen in the fossil record and the later emergence of cultural language use. In other words, although early structural changes in brain regions related to linguistic capacity occurred, it took an extraordinarily long time before those structures were actually used functionally for language.

Indeed, the physical traits typically identified as hallmarks of human evolution—such as bipedal locomotion and reduced canine teeth—were also necessary precursors for the eventual acquisition of speech, yet these changes occurred more than five million years ago. As discussed earlier, brain size only began to surpass that of apes around 2.5 million years ago with Homo habilis. Later, Neanderthals, who lived about 100,000 years ago and were contemporaries of Homo sapiens, possessed large brains and apparent language areas, but their tools showed virtually no progress over tens of thousands of years. Because of this lack of innovation, anthropologists generally believe that Neanderthals did not have fully developed language. In contrast, the “Cultural Big Bang” associated with Homo sapiens—marked by innovations such as hunting tools, ornaments, cave paintings, and symbolic art—is thought to have arisen from the emergence of linguistic ability (Diamond, 2017). Yet, as Yamagiwa (2008) notes, how this sudden technological and cultural revolution occurred remains unknown, and language itself remains one of the greatest mysteries.

The Human Infant as a “Fetus”

Let us return to Eccles’s discussion. Section 5 of Chapter 5 in “Evolution of the Brain” is titled “ Consequences of the brain enlargement in hominid evolution.” It begins with the issue of brain size and childbirth. While language and intelligence are undoubtedly crucial aspects of human uniqueness, this series focuses primarily on emotional and life-cycle characteristics. Eccles’s fifth section directly addresses these aspects.

Citing evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould, Eccles notes that human infants are unique in being born with brains that are small relative to the adult size. Gould argued that if human fetuses were to continue developing their brains to the same level as other primates before birth, pregnancy would need to last several more months—or even up to a year longer—and the resulting brain would be too large to pass through the birth canal. Therefore, humans are born while still small enough to be delivered, meaning that human infants should be regarded as essentially “fetal” in nature (Gould, 1977).

This observation is crucial for understanding the uniqueness of early human development. Rephrased, it implies that the natural gestation period for humans would ideally be about a year and a half (nine months plus an additional seven to twelve months). In this sense, the human infant can be regarded as remaining “fetal” for roughly nine months after birth. Gould emphasized that calling a human baby a “fetus” is not a mere metaphor. For example, the ends of limb and finger bones in newborns remain unossified—just as in fetal monkeys. He further noted that during the first year of life, the growth pattern of a human infant resembles that of a fetal primate rather than that of a newborn primate.

According to Gould, zoologist Adolf Portmann, who proposed the theory of “physiological prematurity,” argued that because humans are learning animals, they are born early so that their still-flexible brains can be exposed to rich environmental stimuli outside the womb. Gould, however, took a more mechanical stance—one that Portmann might have dismissed as crude—suggesting that humans are simply born early because, if birth were delayed another year, the enlarged brain would be too big to pass through the birth canal.

Why Human Babies Are “Like Fetuses”

Gould’s obstetric explanation is no doubt valid. Eccles likewise writes that the earlier timing of birth coevolved with increasing brain size to ensure that the fetal head remained small enough to pass through the maternal pelvis. However, beyond this anatomical adaptation, there likely existed an evolutionary necessity intrinsic to the human species. Evolutionary biologists such as Gould often emphasize the difficulty of human childbirth, yet they also acknowledge the corresponding physical adaptations on both the fetal and maternal sides—such as the molding of the infant’s skull at birth and the sex differences in pelvic structure.

Portmann’s perspective seems aligned with mid-20th-century learning theory, yet I would argue that, beyond environmental stimulation, what is truly vital for the human infant is the early mother–infant relationship. Modern developmental psychology and neuroscience, developed since Portmann’s time, have clarified much about early childhood development, and this is a topic I will revisit later in this series.

The Human Brain Grows Fourfold

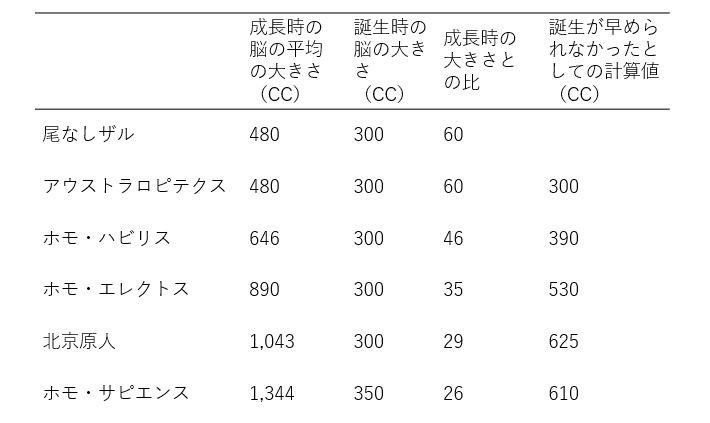

So how large is the human brain, in concrete terms? Eccles presents a table comparing the brain sizes of great apes and humans at birth and in adulthood (Table 1).

Table 1: Brain Size at Birth and Adulthood

Source: John Eccles (translated by Masao Ito) (1990) Table 5-2

As noted earlier, in both great apes and Australopithecus, brain size at maturity was about 480 cc. In fossil humans, brain volume gradually increased, reaching about 1,344 cc in Homo sapiens—roughly a threefold increase. However, what deserves special attention is the brain size at birth: the difference between great apes and modern humans is minimal (300 cc vs. 350 cc). In other words, the newborn brain of a great ape already reaches about 60% of its adult volume, whereas in humans it is only about 26%. Thus, while the human newborn’s brain is almost the same size as that of a newborn ape, the human brain eventually grows to about four times its birth size, compared with only about twice in apes.

References

- Eccles, J. C.(1989).Evolution of the Brain: Creation of the Self. Routledge. エックルス, J, C. 伊藤正男(訳)(1990).脳の進化 東京大学出版会

- Diamond, J. (2014). The Third Chimpanzee for Young People: On the Evolution and Future of the Human Animal. Seven Stories Press. Diamond, J. Akiyama Masaru (translator) (2017). The Third Chimpanzee for Young Readers. (Trans. Masaru Akiyama). Sōshisha Bunko. (ダイアモンド,J. 秋山 勝(訳)(2017).若い読者のための第三のチンパンジー―人間という動物の進化と未来 草思社文庫)

- Yamagiwa, J. (2008). Jinrui Shinkaron: Reichourui-ron kara no Tenkai [Human Evolutionary Theory: A Primatological Perspective]. Shōkabō. (山極寿一(2008).人類進化論-霊長類学からの展開 裳華房)

- Gould, S, J. (1977). Ever Since Darwin: Reflection in Natural History. W.W. Norton. グールド,S, J. 浦本昌紀・寺田 鴻(訳)(1995).ダーウィン以来—進化論への招待 早川書房