EN-ICHI Opens Up the Future of Family and Community

Series: The Human Life Cycle and the Family (1) Human History from the Perspective of Brain Evolution

I am a psychologist—my specialties are neuropsychology and clinical psychology—and I have long been interested in how the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences each conceive of the human being. Referring to insights that range from the humanities to the natural sciences reflects my own inclinations, but it also fits the nature of psychology itself: the discipline began with a philosophical concern for individual cognition, then branched in one direction toward the study of social relationships and in another toward areas that intersect with brain science and computer science. In this series, I will explore the characteristics of human beings and families while surveying this wide scholarly terrain.

- Neurophysiologist John C. Eccles

- The Modern Human Limbic System

- Evolving Toward Greater Sensitivity to Positive Affect

- The Emergence of the Genus Homo

Neurophysiologist John C. Eccles

To set the stage for this series, I would like to begin with a single figure from a specialized volume—an image so striking to me that I have already discussed parts of it in several papers. Up to now, however, I have mostly touched on one aspect of what the figure implies. This time, I will look more carefully at the author’s broader argument surrounding that figure.

The book is titled "脳の進化"; the original English title is "Evolution of the Brain: Creation of the Self "(1989), which makes clear the author’s focus on brain evolution and the emergence of self-awareness. Its author is the neurophysiologist J. C. Eccles, a Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine. Quotations here are taken from the Japanese translation by Masao Ito(伊藤正男) (1990). The book synthesizes findings not only from medicine and physiology but also from paleontology, archaeology, philosophy, and psychology, bringing them together from the author’s perspective in a comprehensive treatment of human evolution. The translator, Ito, describes it as a summation of Eccles’s thought, and Eccles himself writes that “for nearly seventy years, my life was, in effect, preparation to write this book.” What I will examine is only a small portion—some of the discussion in Chapter 5. For anthropological findings on human evolution, I will, as needed, consult the work of Juichi Yamagiwa(山極寿一), one of Japan’s leading primatologists, alongside Eccles’s argument.

Eccles holds that a purely naturalistic account grounded in Darwinian evolution is limited when it comes to explaining the evolution of human self-awareness. He laments that the major works of twentieth-century biologists such as Ernst Mayr, Jacques Monod, and E. O. Wilson have “nothing to say about the evolution of mind.” Having become “captivated” by the question of human evolutionary origins at age seventeen, he returned to it late in life, addressing head-on the evolution of the human brain and mind in "Evolution of the Brain." The book comprises thirteen chapters, the last three of which treat human consciousness—material that is fascinating in its own right. Since my focus here is the distinctive features of the human life cycle, I will concentrate on Eccles’s claims most relevant to that discussion—namely, the section in which the figure appears.

The Modern Human Limbic System

The figure in question appears in the latter half of Chapter 5, “Relationships Between the Limbic System and the Evolution of Reproductive and Emotional Systems,” which addresses the evolution of the human limbic system. Before turning to the figure-specific argument, let me briefly note the first half of the chapter: Section 1, “Some Anatomical Considerations”; Section 2, “The Limbic System and Emotional Expression”; and Section 3, “The Pharmacology of the Limbic System and the Hypothalamus.”

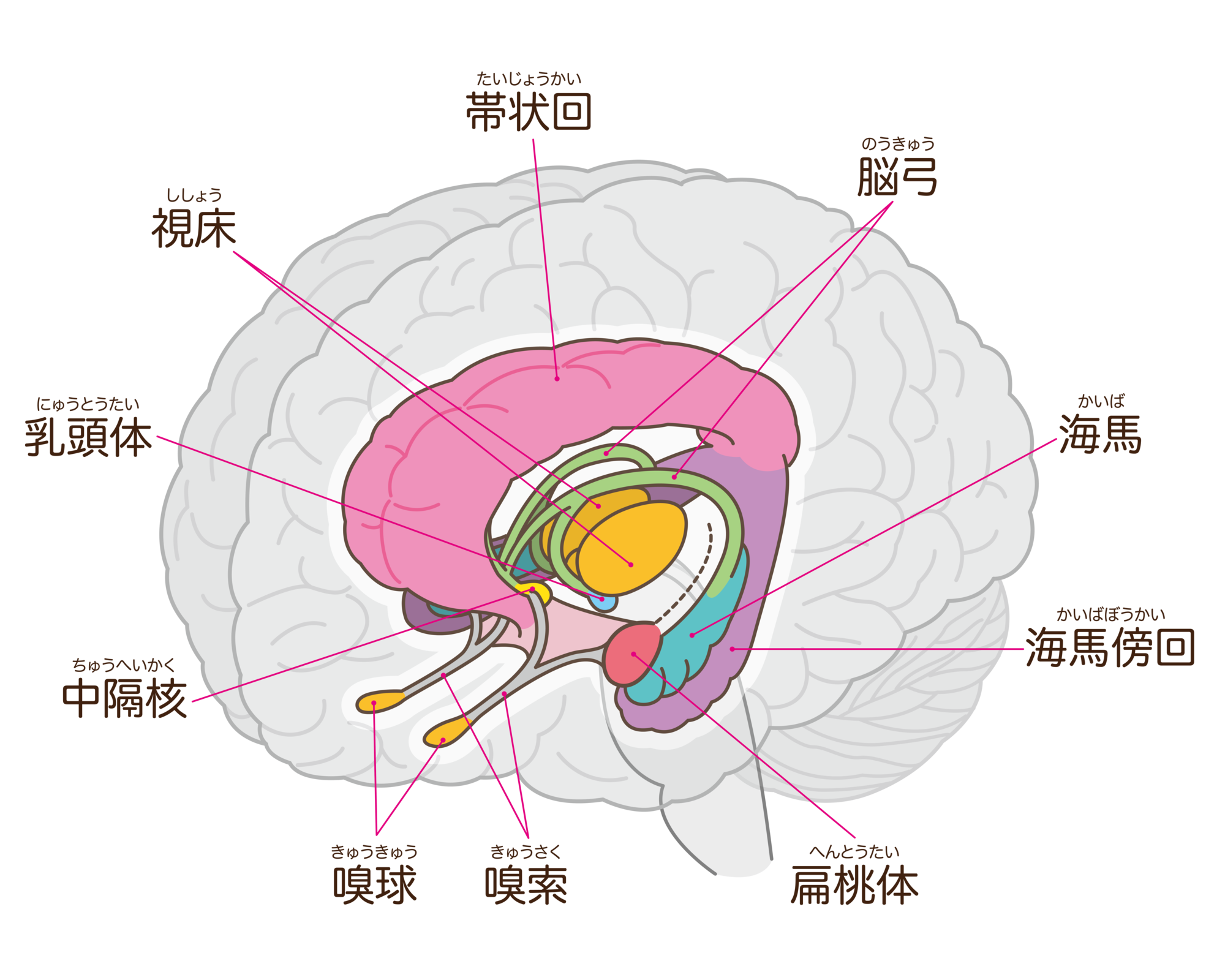

A neuroanatomy text defines the limbic system as “the limbic lobe and its related subcortical structures”(山鳥, 1996). The limbic lobe is cortical and includes the hippocampal formation, the rhinencephalon, the basal forebrain, and the cingulate gyrus. Subcortical components include the amygdala, septal nuclei, epithalamus and hypothalamus, thalamic nuclei, and others. The functions attributed to this constellation—often called the “visceral brain”—include the formation of emotion, maintenance of homeostasis, and regulation of emotional and sexual behavior (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Structure of the Limbic System

Image: PIXTA

Evolving Toward Greater Sensitivity to Positive Affect

In Chapter 5, Eccles discusses the evolution of this structurally and functionally defined system. In Section 4, “Indices of Size of Limbic Components in Primate Evolution,” he notes that two key limbic structures in humans—the septal nuclei and the amygdala—are larger than in other great apes when adjusted for body weight.

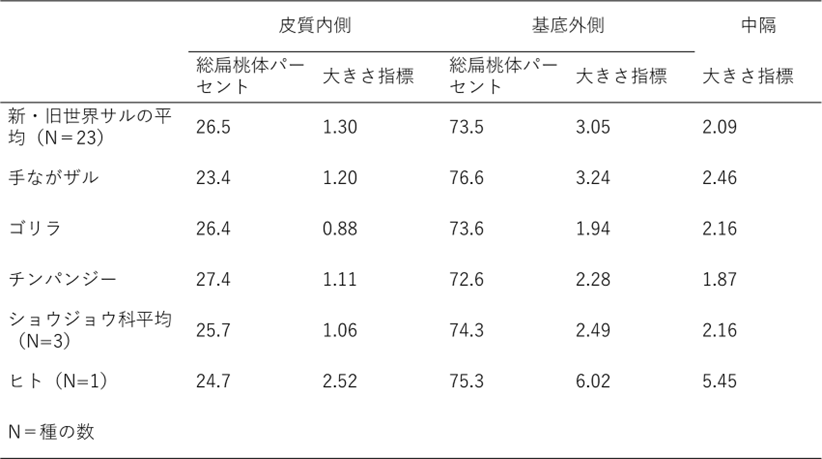

The increase is especially marked in the basolateral region of the amygdala. The medial (cortical) portion is phylogenetically older, whereas the basolateral portion is newer and is reciprocally connected with the sensory association areas of the neocortex(山鳥,1996). For example, using insectivores as 1.00, the size index for the medial amygdala is 1.11 in chimpanzees and 2.52 in humans, whereas for the lateral portion it is 2.28 in chimpanzees and 6.02 in humans—indicating a pronounced enlargement of the lateral amygdala in our species (Table 1). The septum shows a similar pattern.

Eccles writes that, in human limbic evolution, “those components (the septum and basolateral amygdala) associated with pleasurable, agreeable experience tend to increase, whereas components related to aggression and anger (the medial cortical portions) remain comparatively underdeveloped.”

This is a striking observation. It suggests the possibility that, over the course of evolution, humans became more sensitive to stimuli eliciting positive emotions than to those eliciting negative emotions. If such a trend holds, then when we seek to understand human nature, it encourages us to pursue not only conflict but also coexistence and cooperation as central themes.

Table 1. Comparative Size Indices for the Amygdala and Septum

Source: Eccles, JC (translated by 伊藤正男) (1990) "Table 5.1 Evolution of the amygdala and septum"

The Emergence of the Genus Homo

Eccles’s analysis compares present-day primates with humans, but in the actual fossil record, an increase in cranial capacity becomes evident a little over two million years ago(山極, 2008). Australopithecus garhi, a species on the line leading to the genus Homo, had a brain volume of about 450 cc, comparable to that of great apes. As Yamagiwa notes, “our ancestors, after diverging from the common ancestor with chimpanzees, soon began walking upright and survived for over four million years with ape-like brains (山極, 2008).” Even so, tool marks on nearby animal bones suggest that garhi already used stone tools. Crucially, “only about 100,000 years later, Homo habilis appears with a brain volume exceeding 600 cc,” he writes. Stone tools were likely used to cut meat and break bones. Nutritional improvements afforded by meat eating are thought to have been indispensable for the expansion of the brain, an organ with exceptionally high energy demands. With this enlargement came the emergence of the genus Homo.

References

- Eccles, J. C.(1989).Evolution of the Brain: Creation of the Self. Routledge. (エックルス, J, C. 伊藤正男(訳)(1990).脳の進化 東京大学出版会

- 山鳥 崇(編著)(1996).実用神経解剖学 金原出版

- 山極寿一(2008).人類進化論-霊長類学からの展開 裳華房