EN-ICHI Opens Up the Future of Family and Community

Why Aren’t Young People Getting Married Anymore? (1) Causes of Declining Marriage Rates through the Lens of Family Sociology

Why are so many young people choosing not to get married these days?

Some might point to internal or psychological shifts such as increasing individualism or changing views on love and marriage. Others may recall buzzwords like “Herbivore Men" (young Japanese men who are not aggressive in pursuing romantic relationships or career advancement) or “Parasite Singles.” Still others may link the trend to broader economic and labor-related changes, such as Japan's so-called “Lost Decades” or the impact of the “Employment Ice Age Generation" (people who entered the job market in the 1990s and early 2000s, when the economy was stagnant after the burst of the bubble economy). Because this is such a relatable issue, people often draw from their own experiences and intuitions to explain it. But what explanations have been offered from an academic perspective? Over the next three installments, we’ll explore this question together. In this first part, we’ll look at the causes of the decline in marriage rates as explored in family sociology.

- What Are Delayed and Non-Marriage?

- Value Shifts and Fertility Decline in Western Europe

- Has a Similar Shift in Values Occurred in Japan?

- Issues Yet to Be Fully Examined

What Are Delayed and Non-Marriage?

When rephrased in more academic terms, the question "Why are young people not getting married?" becomes: "Why are delayed marriage and non-marriage increasing?"

Delayed marriage refers to a rise in the average age at which people marry, resulting in a longer period of singlehood. Non-marriage indicates a growing proportion of individuals in each age group who remain unmarried, leading to a rise in the lifetime unmarried rate—the percentage of people who have never married by age 50 (『現代社会学事典』『家族社会学事典』).

Japanese family sociologist Masahiro Yamada has analyzed shifts in average age at first marriage and fertility rates, and identified five distinct phases of change (山田2007:64).

⓪ 1945-50: Post-war confusion followed by a baby boom

① 1950-55: A rapid decline in births

② 1955-75: A period of stability in marriage and childbirth

③ 1975-95: Gradual rise in non-marriage

④ 1995-present: Rapid increase in non-marriage and decrease in the number of children per couple

In Japan, after the immediate post-war baby boom (⓪), the country transitioned from high birth and death rates to a stage of low fertility and mortality (①), followed by a stable period for marriage and childbirth (②). During this time, the lifetime unmarried rate (the proportion of people unmarried at age 50) remained around 2% for both men and women. The average age at first marriage also stabilized around 27 for men and 24 for women, and the typical pattern involved having two children after marriage. This period from 1955 to 1975 overlapped with Japan’s era of rapid economic growth, and the so-called "Baby Boomer Generation" largely followed this life course.

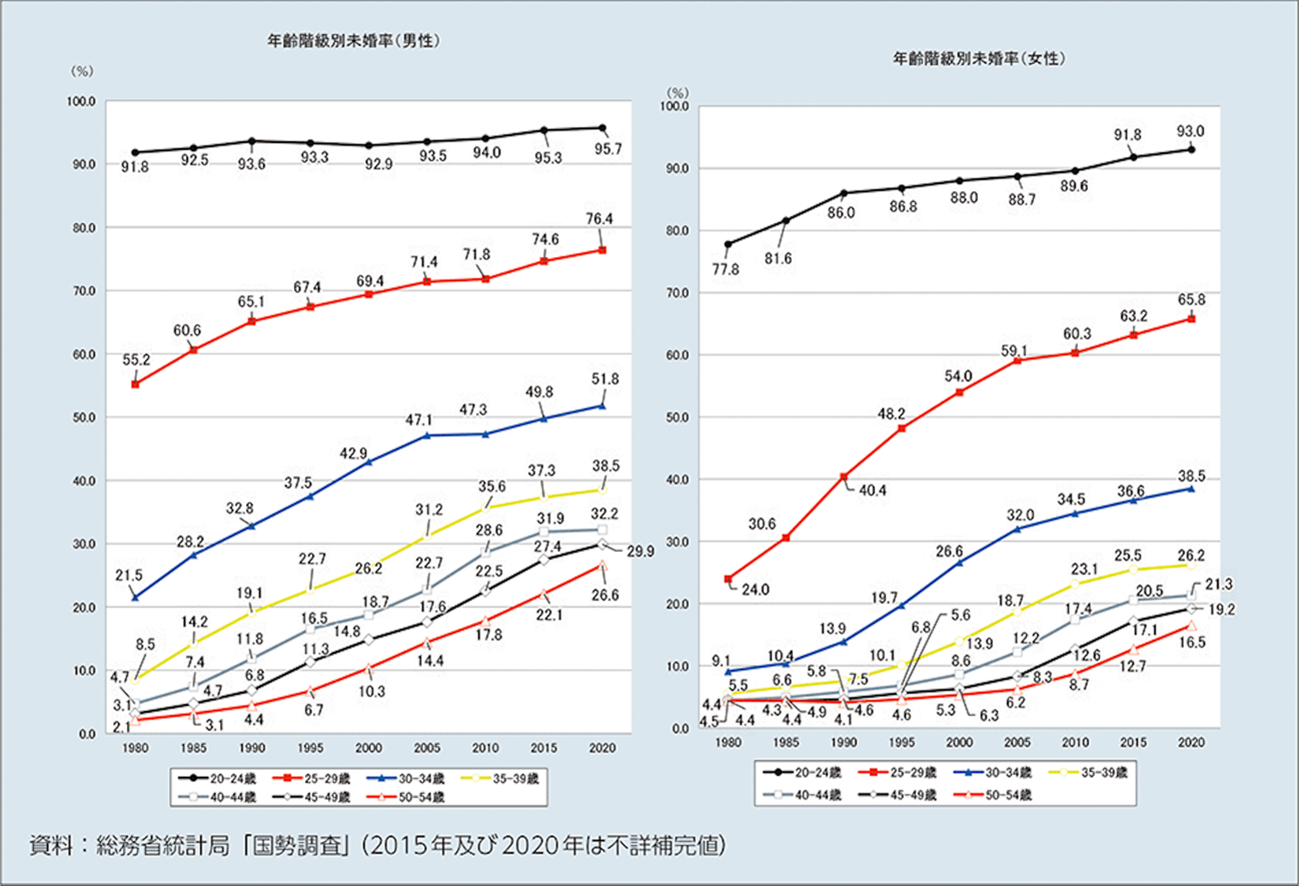

However, starting around 1975 (③), both the average age at first marriage and the proportion of unmarried individuals began to rise. Figure 1 below illustrates this trend, showing the increase in unmarried rates across all age groups since 1980. By 2020, the lifetime unmarried rate had climbed to 26.6% for men and 16.5% for women. In addition, according to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the average age at first marriage in 2024 reached 31.1 years for men and 29.8 years for women, indicating a continuing trend of delayed marriage (厚生労働省2025).

Figure 1. Unmarried Rate by Age Group Over Time

(Source) 2023 edition of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare White Paper, p.8 (令和5年版『厚生労働白書』p.8)

The reason non-marriage is viewed as a problem in Japan is that it is considered a major contributing factor to the country’s declining birthrate (廣嶋 2000; 岩澤 2002, 2008, 2015; 筒井 2023). Two main elements influence fertility trends: the marriage rate (the proportion of people who are married) and the marital fertility rate (how many children are born to married couples). While the marital fertility rate has not shown a significant decline in the past, recent years have seen some decrease. Nevertheless, it is clear that the decline in the marriage rate—that is, the increase in non-marriage—has played a significant role in driving down fertility levels.

Of course, the decision to marry or not is a personal choice, and not something others should interfere with. However, when viewed from a societal perspective, non-marriage is a key driver of low fertility—and with it, population aging—both of which are critical challenges for Japan. For this reason, extensive research has been conducted to explore the factors behind the rise in non-marriage.

Value Shifts and Fertility Decline in Western Europe

Declining birthrates have become a common trend across nearly all advanced nations. In Western European countries, fertility rates began to drop almost simultaneously in the late 1960s, and by the 1980s had fallen below the replacement level—the rate required to sustain population size—where they have largely remained stagnant ever since.

However, in Western Europe, non-marriage is not considered a primary cause of fertility decline. This is because childbirth and marriage have become decoupled in those societies. In that sense, the circumstances in Japan differ significantly from those in Western Europe.

In Western Europe, fertility decline has been attributed to a broader shift in social values. Traditional norms and moral expectations surrounding sexual behavior, cohabitation, marriage and divorce, and childbirth have weakened, giving way to the pursuit of individual self-fulfillment as the most important personal goal. Demographer Ron Lesthaeghe refers to this transformation as a process of secularization and individuation (Lesthaeghe & Surkyn 1988).

As a result, there has been a rise in divorce rates, an increase in non-marital cohabitation, and a growing number of births among cohabiting couples. Notably, “cohabitation” in this context is not seen as merely a prelude to marriage, but rather as a long-term alternative to it. In many Western countries, over 30% of children are born outside of marriage. In these societies, marriage and childbearing are no longer inseparable (J.M. Raymo 2022).

This value-driven transformation and its impact on fertility are captured by the Second Demographic Transition (SDT) theory. According to this theory, fertility decline is not just temporary but structural and irreversible, driven by profound changes in individual values. While the SDT theory has been the subject of criticism, it remains widely accepted as a framework for understanding fertility decline in Europe (河野 2007).

Has a Similar Shift in Values Occurred in Japan?

So, can Japan’s declining birthrate be explained in the same way as in Western Europe—as a result of shifting values? Does the Second Demographic Transition (SDT) theory also apply to Japan?

Demographer Retherford has argued that in Japan, changes in population trends tend to occur before shifts in values, and that the fertility decline observed in the 1970s was driven by socioeconomic factors rather than cultural or attitudinal change (Retherford 1996). According to his findings, the SDT framework may not be applicable to Japan.

That said, this does not mean that no value shifts have occurred in Japanese society. Retherford also noted changes in attitudes regarding women’s social participation and their roles in society.

Japanese demographer Makoto Atoh similarly observed a gradual move toward individualism in the postwar period. He points to a sharp decline in the belief that daughters are obligated to care for elderly parents, a weakening of traditional gender-role attitudes, and a significant rise in the perceived social value of women. These suggest that major changes have occurred in how women’s roles are viewed. However, Atoh also stresses that unlike in Western societies, Japan has not experienced a comprehensive breakdown of traditional values or a full embrace of individualism (阿藤 1997).

More recent studies also highlight the differences between Japan and Western countries in terms of value change. The core features of the SDT in Western Europe—such as the decoupling of marriage and childbirth, the rise of cohabitation as an alternative to marriage, and a significant increase in births outside of marriage—are largely absent in Japan (J.M. Raymo 2022).

In Japan, sociologist Masahiro Yamada once popularized the term “Parasite Singles” to describe unmarried young adults living with their parents (山田 1999). In his work, Yamada points out that despite drastic socioeconomic changes, traditional views on marriage—such as the idea that marriage transforms a woman’s identity or the preference for hypergamy (marrying “up”)—have remained relatively intact. In other words, although the economic landscape has changed, fundamental attitudes toward marriage have been slow to evolve.

Taken together, these studies suggest that Japan has not undergone the kind of deep value transformation seen in Western societies that contributed to their fertility decline. At the very least, there is little evidence to support the idea that changes in values alone can explain the rise in non-marriage in Japan.

Issues Yet to Be Fully Examined

However, the relationship between values and fertility is not as straightforward as it might seem.

As noted earlier, Retherford argued that value changes did not significantly influence fertility trends in the 1970s. At the same time, however, he suggested that the inverse may also be true: that fertility decline itself could lead to changes in values. In other words, rather than value shifts influencing fertility alone, the reverse dynamic is also possible—fertility changes may reshape social values. Moreover, these newly formed values may in turn accelerate further declines in fertility (Retherford 1996). This possibility requires further empirical investigation.

In addition, the social advancement of women since the 1970s—and the accompanying shifts in how society perceives women’s roles—must not be overlooked. As discussed in the previous section, many studies have highlighted changes in values related to women’s status. Atoh has also suggested a connection between rising non-marriage and shifting gender role attitudes (阿藤 1997). In Japan, public discourse has featured two competing narratives regarding women’s social advancement and its relationship to non-marriage and declining fertility. One argument holds that women's participation in the workforce has caused these demographic shifts, while another contends that promoting gender equality and supporting women’s careers is actually the key to reversing fertility decline. These two opposing views continue to coexist in Japanese society. We will examine this issue in more detail in the next installment (Part 2).

[Series] Why Aren’t Young People Getting Married Anymore?

(1) Causes of Declining Marriage Rates through the Lens of Family Sociology

(2) Women’s Empowerment and the Rise in Non-Marriage

Cited literature/Main references

- Akagawa, M. (2004). Kodomo ga Hette Nani ga Warui ka! [What’s Wrong with Having Fewer Children!?]. Chikuma Shobo.

- Ato, M. (1997). Nihon no chōshōshussanka genshō to kachikan hendō kasetsu [Japan’s “ultra-low fertility” phenomenon and the value change hypothesis]. Journal of Population Problems, 53(1), 3–20.

- Hiroshima, K. (2000). Kinnen no gōkei tokushu shusseiritsu teika no yōin bunkaiseki: Fūfu shusseiritsu wa kiyo shite inai ka? [Decomposing the recent decline in the total fertility rate: Has marital fertility not contributed?]. Jinkōgaku Kenkyū [The Japanese Journal of Population], 26, 1–20.

- Iwasawa, M. (2002). Kinnen no kikan TFR hendō ni okeru kekkon kōdō oyobi fūfu no shussei kōdō no henka no kiyo ni tsuite [Contributions of changes in marriage behavior and marital fertility behavior to recent period TFR fluctuations]. Journal of Population Problems, 58(3), 15–44.

- ———. (2008). Shokon・rikon no dōkō to shusseiritsu e no eikyō [Trends in first marriage and divorce and their effects on fertility]. Journal of Population Problems, 64(4), 19–34.

- ———. (2015). Shōshika o motarashita mikonka oyobi fūfu no henka [Non-marriage and changes among married couples that have contributed to low fertility]. In S. Takahashi & H. Obuchi (Eds.), Jinkō genshō to shōshika taisaku [Population phenomena and measures to address low fertility] (pp. 49–72). Harashobo.

- Raymo, J. M. (2022). The second demographic transition in Japan: A review of the evidence. China Population and Development Studies, 6, 267–287.

- Kono, S. (2007). Jinkōgaku e no Shōtai: Shōshika・Kōreika wa Doko made Kaimei Sareta ka [An Introduction to Demography: How Far Have We Explained Low Fertility and Population Aging?]. Chuo Koron-Shinsha.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2024). Kōsei Rōdō Hakusho [White Paper on Health, Labour and Welfare].

- ———. (2025). Reiwa 6-nen jinkō dōtai geppō nenkei (gaisū) no gaikyō [Overview of the annual totals (provisional figures) of the Monthly Vital Statistics Report, 2024]. (Government report).

- Mita, S., et al. (Eds.). (2012). Gendai Shakaigaku Jiten [Encyclopedia of Contemporary Sociology]. Kobundo.

- Japan Sociological Society. (Ed.). (2023). Kazoku Shakaigaku Jiten [Encyclopedia of Family Sociology]. Maruzen Publishing.

- Retherford, R. D., Ogawa, N., & Sakamoto, S. (1996). Values and fertility change in Japan. Population Studies, 50(1), 5–25.

- Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14(1), 1–45.

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. (2021). Reiwa 2-nen kokusei chōsa: Jinkō tō kihon shūkei kekka [2020 Population Census of Japan: Basic tabulation results on population, etc.]. (Government statistics).

- Tsutsui, J. (2023). Mikon to Shōshika: Kono Kuni de Kodomo o Uminikui Riyū [Non-Marriage and Low Fertility: Why It’s Hard to Have Children in This Country]. PHP Institute.

- Yamada, M. (1999). Parasaito Shinguru no Jidai [The Age of “Parasite Singles”]. Chikuma Shobo.

- ———. (2007). Shōshi Shakai Nihon: Mō Hitotsu no Kakusa no Yukue [Japan as a Low-Fertility Society: The Future of Another Inequality]. Iwanami Shoten.