EN-ICHI Opens Up the Future of Family and Community

Could Your Unexplained Symptoms Be Rooted in Your Family Relationships? Understanding the Mind–Body Connection through Family Therapy

We spoke with Dr. Hasebe (pseudonym), a board-certified family physician, about the “mind–body connection” from the perspective of family therapy. Unexplained physical or emotional symptoms are sometimes closely intertwined with a person’s family relationships. The EN-ICHI editorial team has compiled and organized Dr. Hasebe’s insights below, from the basic theory of family therapy to real-life cases and practical tips you can use at home.

- Introduction

- A Couple’s Story: How Physical Pain Masked a Marital Rift

- Family Therapy: Focusing on Relationships Rather than Individuals

- Three Tips for Reflecting on Your Own Family Relationships

- Conclusion: Building Better Relationships

Introduction

Unexplained physical pain or emotional distress may, in fact, be deeply linked to the way you relate to your family members. That idea might sound a little surprising at first. But in the day-to-day practice of psychosomatic medicine, working closely with patients, I am constantly reminded of just how strongly the mind, the body, and our closest relationships—our families—affect one another.

Today, the forms that families take are highly diverse. The so-called “standard household” of a couple with children accounted for only 25% of all households in 2022. Single-person households are now the most common type, and the number of couples without children is roughly the same as that of nuclear families. Even so, regardless of the form a family takes, one thing remains unchanged: the quality of those family relationships has a powerful impact on our physical and mental health.

In this article, I would like to explore the mysterious connection between mind and body through the lens of family therapy and offer some concrete clues to help you reflect on your own family relationships.

A Couple’s Story: How Physical Pain Masked a Marital Rift

Before diving into theory, let me start with a single case example. I firmly believe that walking through a concrete story is one of the most effective ways to really feel how family relationships can affect both mind and body.

Case Presentation

The patient was a middle-aged woman I saw in my outpatient clinic. After her daughter got married and moved out a few years earlier, the patient began to suffer from unexplained, widespread pain throughout her body. She visited multiple hospitals, but nothing eased the pain.

Around the same time, her relationship with her husband deteriorated rapidly. Their arguments grew more intense and, eventually, the situation escalated to the point that the police became involved. After that, the couple started living separately.

In the consultation room, she spoke about the suffering caused by her pain and her deep mistrust of her husband. “He must be having an affair. I’m sure of it. I can only think about divorce now.” She insisted on this point very strongly. At the same time, a psychiatrist at another clinic suggested she might be suffering from a delusional disorder. She felt that no one truly understood how much she was suffering and carried a profound sense of loneliness.

Dilemmas in Clinical Practice

In working with this case, I experienced many conflicting emotions of my own. When we are faced with ethical issues in a family—such as infidelity or divorce—our personal values and views on family are inevitably stirred up, even though we are there as medical professionals. I realized that these internal reactions were getting in the way of understanding the patient as a whole person. I also felt very keenly how this made it harder to build a trusting relationship with her. This kind of experience is emblematic of the dilemmas that health professionals often face in clinical practice. Ethical issues in a family can send ripples through our own inner world as clinicians, sometimes shaking our calmness and objectivity.

In moments like this, a powerful compass is the approach known as “family therapy”.

Family Therapy: Focusing on Relationships Rather than Individuals

Family therapy is one approach within the broader field of psychotherapy. Its defining feature is that it does not treat a problem as something belonging to the individual alone. Instead, it views that problem within the context of the entire family as a system of relationships. The goal is to reorganize those relationships into a healthier pattern so that, as a result, the individual’s symptoms or difficulties gradually improve.

When we face ethical problems within a family, having this relational perspective makes it easier to see the underlying issues. Topics like infidelity or divorce tend to provoke strong value judgments, even in professionals. But when we look at them not just as matters of “someone’s fault” or purely moral issues, and instead reframe them as “relationship difficulties,” it becomes easier to engage with the situation calmly and from multiple angles.

Similarly, when we think about an individual’s physical or psychological symptoms, family therapy encourages us not to look for “the cause” solely inside the person. By widening our view to include the entire system of relationships that person lives in and is affected by, we often begin to see new pathways toward solutions that were previously hidden.

Below, I will explain the basic ideas behind family therapy.

Theoretical Background: Systems Theory

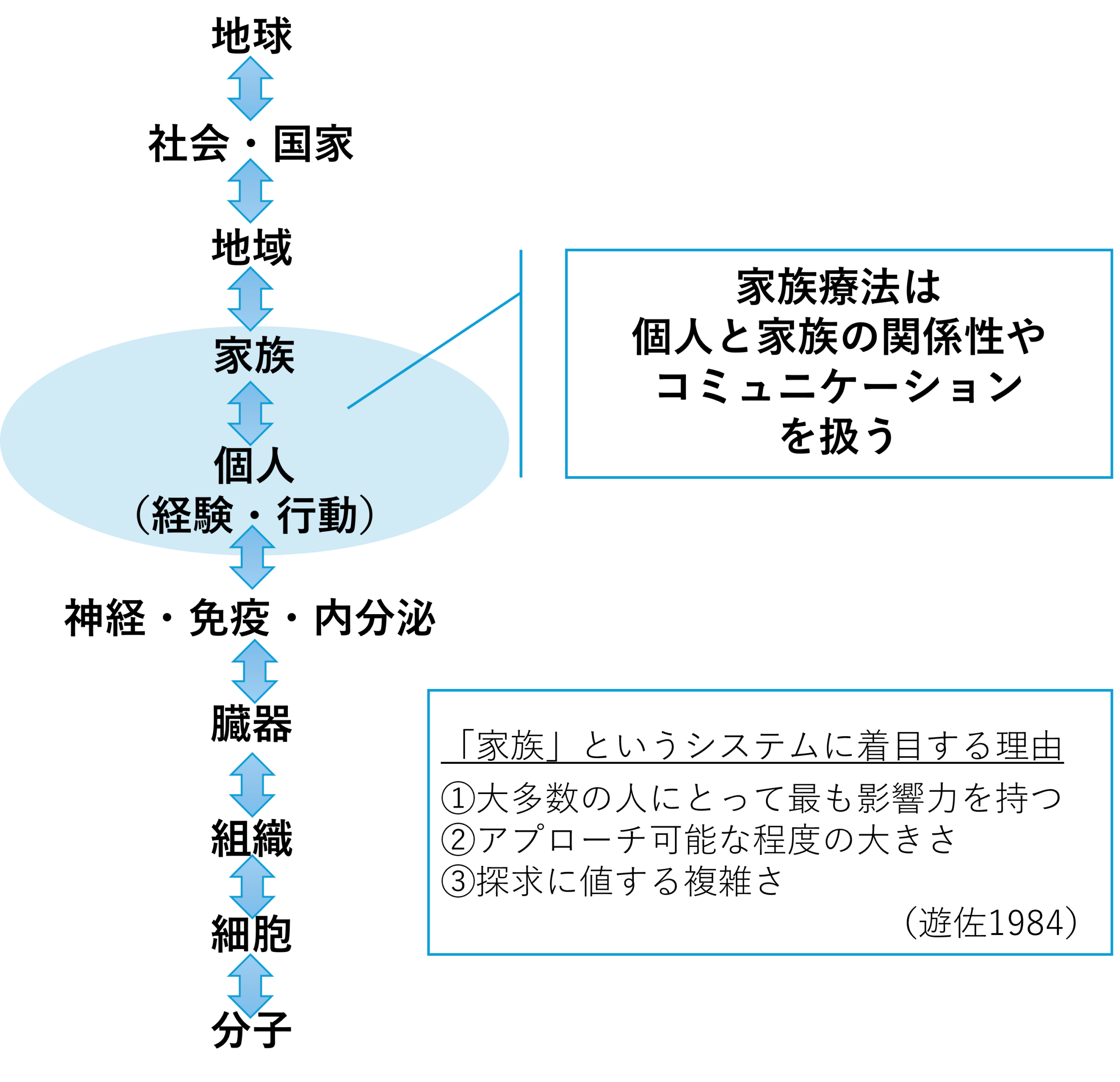

TThe foundation of family therapy lies in what is known as "systems theory". Systems theory views human beings and society not as a collection of isolated parts, but as networks of relationships and mutual interactions.

Systems theory has two main characteristics.

1) A Reductionist and an Integrative View

In medicine, we often “reduce” problems to smaller units—organs, tissues, cells—in order to find causes and select treatments. This reductionist perspective is essential. At the same time, we also need an integrative perspective: how does this person’s illness make sense in the broader context of their family and society? Both the “parts” and the “whole” matter. Systems theory stresses the importance of holding these two viewpoints together.

2) Emphasis on Mutual Interaction

In a system, elements do not influence one another in just one direction; they interact bidirectionally. For example: ・Stress at work (a social system) may lead to overeating and heavy drinking, which in turn can cause illness (an individual system). ・Conversely, once a person becomes ill, they may be forced to take time off work, which can then affect their workplace relationships (again, the social system). In this way, everything is understood as being linked in a chain of interactions.

Why Focus on “Family”?

We live within many different relational systems: workplaces, local communities, even nations. Among these, family therapy places particular emphasis on the unit of the family, and there are clear reasons for this (Figure 1). Clinical psychologist Yasichiro Yusa explains these reasons in three key points (Yusa, 1984):

1) The most influential system: For most people, the family is the relationship they are involved in most deeply and for the longest time, beginning in early childhood. Its impact is enormous.

2) A manageable size for intervention: While changing a whole nation or society is extremely difficult, working with the relationships in a single family sitting in front of us is a realistic and meaningful place to intervene.

3) Complex enough to warrant deep exploration: Family relationships are highly complex, and many people struggle with them. Precisely because of this complexity, they merit careful study and exploration.

Figure 1. Focus on the Family as a System

Source: Created by Dr. Hasebe

Applying Family Therapy to the Case: Pathways Toward Change

Now, let us go back to the couple introduced at the beginning and look at their situation through the lens of family therapy.

As the consultations went on, there came a day when the patient said something quite different from what she had been saying before: “When I went to my husband’s place, everything he needed for daily life was there, and I suddenly felt very lonely. Deep down, I really want to know whether his heart has already left me. Honestly, there’s still a part of me that wants to get back together.” It was the first time she spoke not in terms of blame, but from her own true feelings.

Sensing an opening, I suggested: “Would you be willing to see this pain and anxiety as a problem of your relationship as a couple, rather than just your individual symptoms?” We then arranged for joint sessions with both husband and wife.

Through those sessions, a particular pattern in their relationship came to light: a mismatch in how they expressed love.

What the wife wanted: She wanted verbal confirmation—words that would answer the question, “Do you really care about me?”

What the husband was doing:After she became ill and could no longer manage housework, he had been cooking every day and providing care for several years, expressing his love through actions.

The wife craved words; the husband expressed love through actions. Both cared deeply for each other, yet the difference in how they expressed that love led each to conclude, “My partner doesn’t really care about me,” and their hearts drifted apart.

My role was, in a sense, that of an interpreter. By “translating” the feelings behind each person’s behavior and feeding that back to the other, the couple slowly began to understand each other’s intentions. After many conversations, with conflicts along the way, they eventually recovered to the point that they decided to go on a trip together. After the trip, the wife shyly told me:“I realized my husband is actually quite romantic.” Not long after that, her widespread pain disappeared as if it had never existed, and the couple moved back in together.

This case clearly illustrates the deep connection between mind and body: physical pain can be closely linked to family relationships and psychological factors, and as the relationship improves, symptoms may also ease. So, what kind of perspectives can help us improve our own relationships? Below are three practical tips.

Three Tips for Reflecting on Your Own Family Relationships

From here, I would like to offer three specific perspectives that can help you objectively reflect on your own family relationships and gently steer them in a healthier direction. The concepts are somewhat technical, but I will explain them in everyday language so that anyone can apply them to their own life.

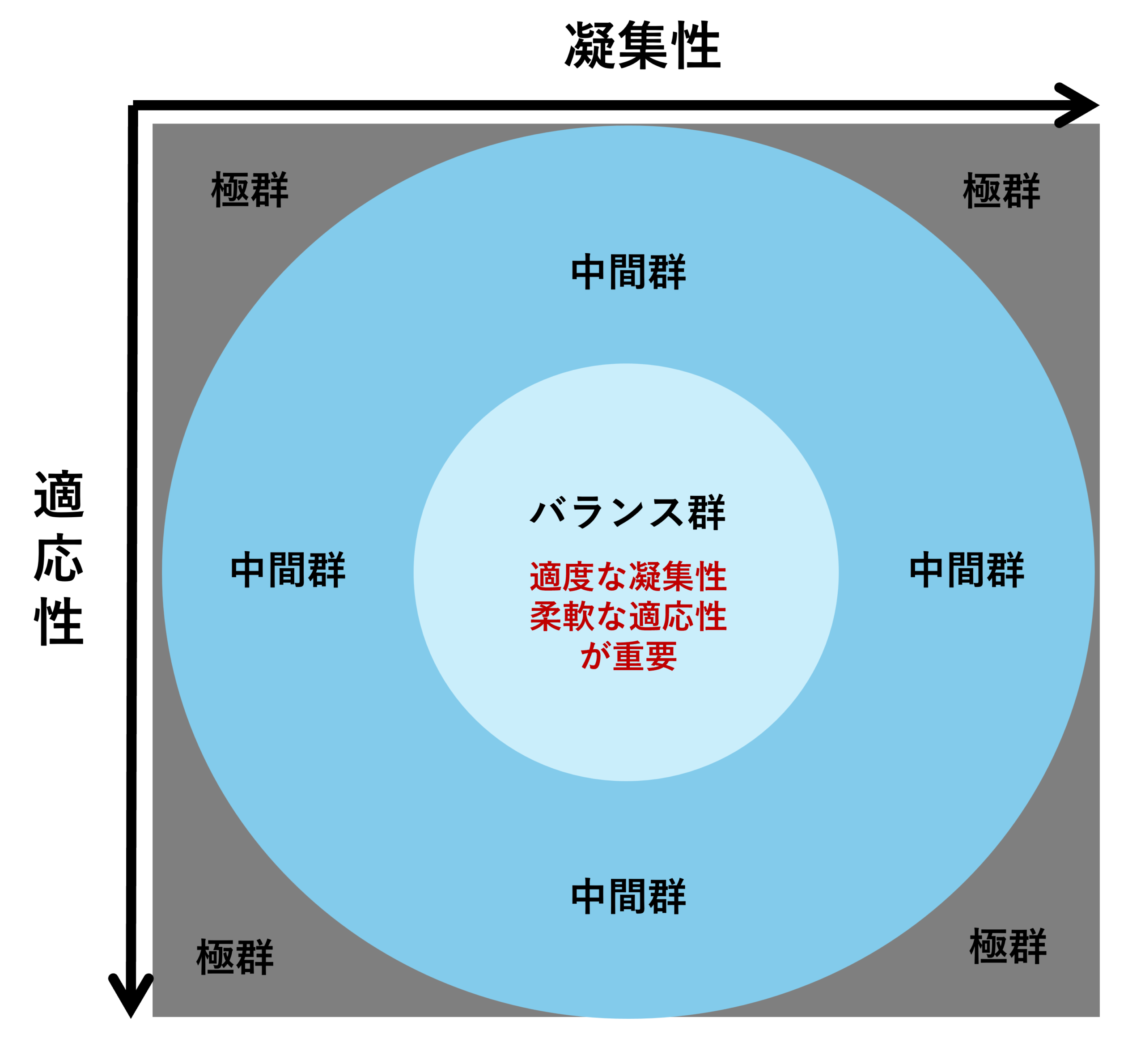

Tip 1: Assess Where Your Relationships Stand Now (The Circumplex Model))

A well-known framework for assessing family relationships is the Circumplex Model. It evaluates the current state of a family along two axes: cohesion (emotional bonding) and adaptability (flexibility in rules and roles).

The Two Axes

* Cohesion (“kizuna”): The strength of emotional bonds among family members.

* Adaptability (“kajitori” – steering): The family’s ability to flexibly change its rules and roles in response to changing circumstances.

<Four Levels of Cohesion>

1. Disengaged: The family is fragmented and emotionally distant.

(e.g., Even when they are in the same room, everyone is just on their smartphone.)

2.Separated: Members are mostly independent but connect when necessary.

(e.g., They usually act separately, but still go on family trips together)

3. Connected: Members are close and share time, while still respecting each person’s autonomy.

(e.g., They eat dinner together, then each spends the rest of the evening as they like.)

4. Enmeshed: Boundaries are blurred and involvement is excessive.

(e.g., Family members do everything together, and individual wishes are not respected.)

Both “connected” and “enmeshed” look close on the surface, but there is a crucial difference: in an enmeshed family, people constantly monitor and try to control one another.

<Four Levels of Adaptability> (Using bedtime rules for children as an example)

1. Rigid: Rules are absolute and never change.

(e.g., “You must go to bed at 9:00 sharp. If you don’t, you will be punished.”)

2. Structured: There are clear rules, but they can be adjusted when needed.

(e.g., “Bedtime is usually 9:00, but on Friday nights you can stay up a bit later.”)

3. Flexible: Rules have a broader range and are applied with flexibility.

(e.g., “Let’s aim to go to bed sometime between 8:00 and 10:00.”)

4. Chaotic: There are no clear rules and no consistency.

(e.g., “You can go to bed whenever you want; staying up late is totally fine.”)

Figure 2. Cohesion and Adaptability

Source: Created by Dr. Hasebe

In this model, families that are not at the extremes (disengaged/enmeshed, rigid/chaotic), but instead fall within the middle two levels (separated/connected, structured/flexible), are called balanced families and are considered the most functional and healthy. In other words, “appropriate emotional closeness” and “appropriate flexibility” are the two key ingredients of a healthy family relationship.

Tip 2: Recognize That Relationships Are Always Changing (The Family Life Cycle)

Family relationships are not fixed; they are always changing over time. The concept of the family life cycle helps us understand this ongoing process of change.

Life Cycle Transitions as “Crises”

Over the course of a lifetime, we experience various transition points: getting a job, getting married, having children, seeing our children leave home, and more. In family therapy, these turning points are referred to as crises. “Crisis” here carries both meanings: risk and opportunity—in other words, “a turning point that can be either dangerous or fruitful.” If a family fails to adjust its roles and rules at these points, it can slide into difficulty (risk). But if it manages these transitions well, the relationships can deepen (opportunity).

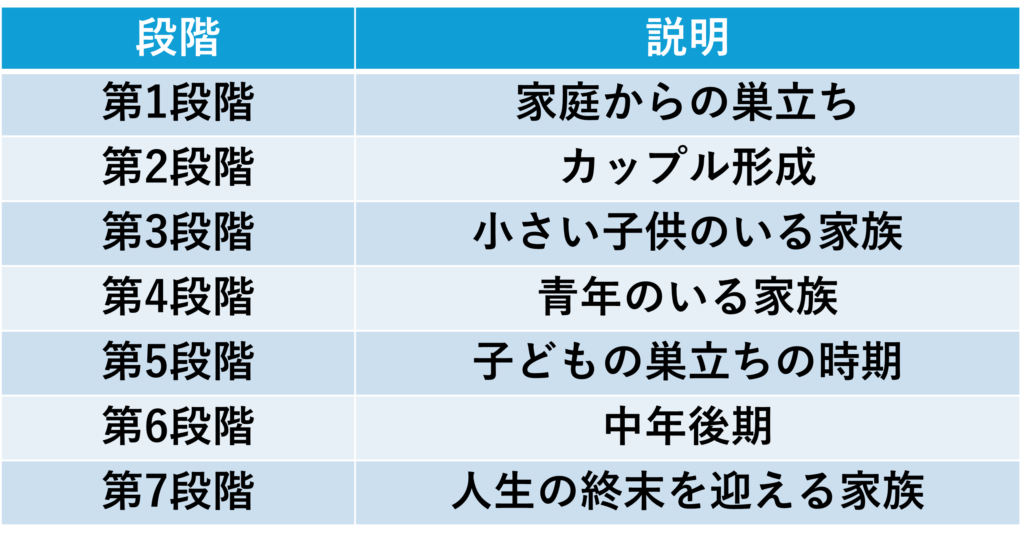

Stages of the Family Life Cycle

Lives differ from person to person, but when we analyze them, they can broadly be grouped into seven stages (see Table 1).

Table 1. Stages of the Family Life Cycle

Source: Created by Dr. Hasebe

For example:

Stage 1: Launching (Leaving home)

Gaining psychological and financial independence from one’s family of origin, forming peer relationships, and developing a personal worldview.

Stage 2: Couple Formation

Negotiating shared values and household rules with a partner and building a new family unit.

Stage 3: Family with Young Children

Discussing the division of roles in childrearing, housework, and finances, and re-adjusting relationships with extended family.

Stage 4: Family with Adolescents/Young Adults

Supporting children’s independence and shifting the parental role from “taking care of” to “providing support.”

Stage 5: Post-launching (Empty nest)

As active childrearing ends, reconstructing the couple’s relationship and searching for new life goals.

Stage 6: Mid- to Late Adulthood

Facing physical decline and caring for aging parents, while redefining social roles and sources of meaning.

Stage 7: End of Life

Transitioning from being the one who supports others to being the one who is supported, facing aging and mortality, and integrating the story of one’s life.

The couple in our opening case was in Stage 5: Post-launching, when children leave home. This is also the stage when “gray divorce” often occurs. Each stage comes with its own set of typical challenges, created by changes in family roles and relationships.

“Life Is Like a Spiral Staircase”

A child psychiatrist once said, “Life is like a spiral staircase.” From above, it may look as if we are going around in circles, passing the same spot again and again. But from the side, you can see that we are, in fact, gradually moving upward. Life is a process of encountering and working through new challenges, growing both as individuals and as families. Rather than fearing change, it is important to keep adjusting our relationships as we climb.

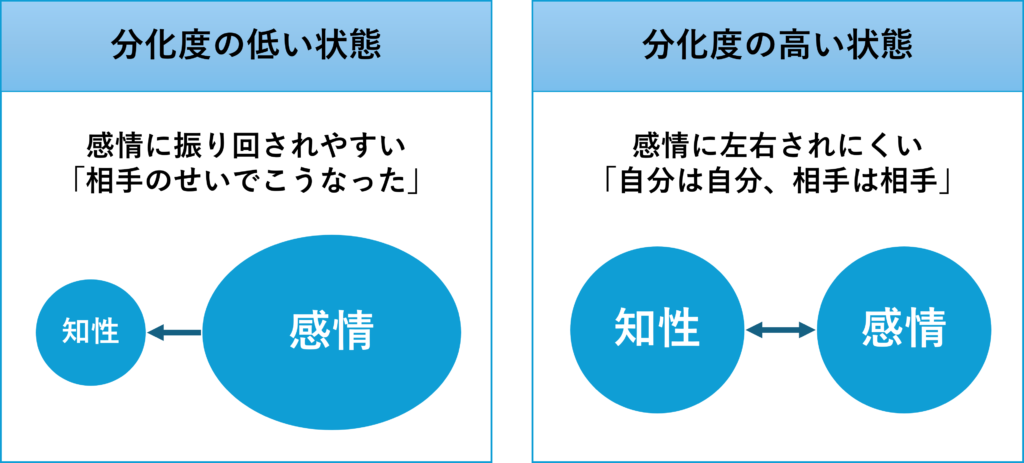

Tip 3: Understand That Relationship Patterns Are Transmitted (Differentiation of Self).

Patterns of relating that repeat within a family can be passed down across generations. The concept that helps us understand this phenomenon is called differentiation of self.

What Is Differentiation of Self?

Differentiation of self refers to a person’s ability to balance thinking (reason) and feeling (emotion).

A low level of differentiation means that thinking and feeling are not well balanced. People are easily swept away by emotion and tend to think, “It’s all because of what the other person did.” A high level of differentiation means that thinking and feeling are relatively well balanced. People are emotionally autonomous and can calmly hold the idea, “I am me, and the other person is the other person.”

Figure 3. Level of Differentiation of Self

Source: Based on Bowen, M. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. New York: Jason Aronson; 1970, adapted by Dr. Hasebe.

Impact on Interpersonal Relationships

A person’s level of differentiation has a major impact on how they form relationships. With low differentiation, people may either depend too heavily on others or, conversely, avoid closeness and become distant and defensive. With high differentiation, people are more likely to maintain healthy boundaries: they can respect the other person while also voicing their own opinions, building flexible relationships with appropriate distance.

Intergenerational Transmission

Levels of differentiation tend to be learned from parents and transmitted from one generation to the next. For example, couples with a low level of differentiation struggle to tolerate tension between them. To reduce their own anxiety, they may unconsciously draw their child into their problems—becoming overly involved with the child to avoid facing the marital issues directly. Children who grow up in such an environment do not have many chances to learn how to separate thoughts and feelings. They may reach adulthood without developing a higher level of differentiation and then end up choosing a partner with a similar level, continuing the same patterns into the next generation.

To break this chain, it is crucial—especially when emotions run high—to consciously take a step back and remind ourselves: “The other person is the other person. I am me.”

Conclusion: Building Better Relationships

In this article, we have looked at the deep connection between physical/mental symptoms and family relationships through the perspective of family therapy. Let us briefly recap the key points:

1. Assess where your relationships stand now (Circumplex Model): Are the “emotional bonds” and “flexibility in rules and roles” reasonably balanced?

2. Recognize that relationships are constantly changing (Family Life Cycle): Life transitions are not just risks; they are also opportunities to revisit and strengthen relationships.

3. Understand that relationship patterns are transmitted (Differentiation of Self): When emotions run high, try to pause and think, “I am me, and the other person is the other person.”

Families differ in composition and lifestyle. Yet, no matter what form a family takes, the central issue is the quality of the relationships within it. If you are currently struggling with unexplained physical or emotional symptoms, it may be worth gently shifting your perspective and taking a fresh look at your closest relationships. You might find, hidden within them, important clues for keeping both your mind and body healthy.

References

- Yusa Y. Kazoku ryōhō nyūmon: Shisutemuzu apurōchi no riron to jissai [Introduction to Family Therapy: Theory and Practice of the Systems Approach]. Tokyo: Seiwa Shoten; 1984.(遊佐安一郎. 家族療法入門:システムズアプローチの理論と実際. 東京:星和書店;1984.)

- Wakabayashi H, Miyamoto Y, Tanaka M, Yamada U, Matsushita A. Radā to jirei kara manabu kazoku shikō no kea [Family-Oriented Care Learned from Ladders and Case Examples]. Tokyo: Chugai Igakusha; 2024.(若林英樹, 宮本侑達, 田中道徳, 山田宇以, 松下明. ラダーと事例から学ぶ家族志向のケア. 東京:中外医学社;2024.)

- McDaniel SH, Campbell TL, Hepworth J, Lorenz A. Family-Oriented Primary Care. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2005.

- Olson DH, Portner J, Lavee Y. FACES III: Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales. St Paul: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota; 1985.

- McGoldrick M, Gerson R, Petry S. Genograms: Mapping Family Systems. In: McGoldrick M, Gerson R, Petry S, editors. Genograms: Assessment and Intervention. 3rd ed. New York: WW Norton; 2008.